User:Vilimaka/Climate change and the Pacific Islands

| Work in progress, expect frequent changes. Help and feedback is welcome. See discussion page. |

| Home | TRAM | 3D Periodic trends | Climate change education curriculum | Teaching Primary School Science | Teaching Science in the Secondary School classroom | My Sandbox | My L4C course home page| |

Today's date: 23 April 2024

Contents

- 1 The Pacific Islands

- 2 Recent changes in the Pacific

- 3 What is global warming?

- 4 Re-orientaing the curriculum to enhance the relevance and inclusiveness of teaching and learning of Climate change

- 5 Climate change and Education for Sustainable Development

- 6 The current challenges to effective Climate change curriculum initiatives in the Pacific

- 7 Re-orienting the curriculum to combat climate change

- 8 Summary

- 9 Web Resources

The Pacific Islands

The Pacific Islands consist of many islands that scattered across the Pacific Ocean. Some of these islands are big and high but most are small and low-lying atolls and are barely a few metres higher than the high-tide mark.

Recent changes in the Pacific

Society is changing in response to events that are happening in the environment. And one of the most effective and responsible avenue for responding to events in our environment is through education (both formal and informal). For example, formal education (teaching, learning, and the curriculum) is ever changing in response to many global challenges. Be it the challenges of the 9/11 in the US or those that were experienced by the people of western Viti Levu, Fiji, as a result of the flash floods in January 2009, the response of education is a reflection of society’s aspiration for a better world.Many Pacific Island countries are already feeling the impact of global warming and climate change. Here are some of our recent experiences:

Coastal flooding

On Majuro atoll in the Marshall Islands, the airport has flooded several times, despite a two-metre seawall. In Tuvalu and Kiribati, surges over seawalls, causeways and roads are commonplace. The islets of Tebua and Bikeman off Tarawa atoll in Kiribati have vanished (Moore, 2002).

Increase incidence of diseases

We love living close to the sea, but with frequent tidal surges, the tide has reached many peoples' pig-styes and toilets. Over the past decade, malaria has broken out in the highlands of Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. Some of these areas are 2000 metres above sea level, where it was previously too cold for malaria mosquitoes to survive. There have been recent outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases, such as dengue fever, in French Polynesia, Fiji and Samoa (Moore, 2002).

Drought and famine

In 1998 drought wiped out two-thirds of the sugar cane crop in Fiji. Sugar cane is a major source of income for Fiji Islanders. In the same year, drought halved the squash harvest in Tonga. Water shortages are becoming commonplace in Tuvalu, Kiribati, Federated States of Micronesia, Samoa and Papua New Guinea (Moore, 2002).

Greater cyclone threats

Tropical cyclones (or typhoons) are becoming stronger and more frequent. In 1997 a super typhoon, Paka, hit Guam while three other super typhoons (Joan, Ivan and Keith) roamed the north Pacific Ocean (Moore, 2002). Within a span of five weeks from February to March 2005, four tropical cyclones hit the Cook Islands. The three in February (Meena, Olaf and Nancy) had devastating effects; the fourth (Percy) in early March was the strongest and most destructive of all of them. In December 2006 to January 2010, many tropcial cylones caused havoc in the eastern Pacific Islands of Aitutaki (Cook Islands), Samoa, Fiji and Tonga. The image on the right shows tropcial cyclones Ului and TC Tomas.

Eroding burial grounds

Our burial grounds are sacred to us, but the sea is taking many of them away. In Niue, Palau, Majuro, Tuvalu and Kiribati, burial grounds are crumbling into the sea (Moore, 2002).

Coral bleaching

In 1998 in Palau, there was bleaching of about 75% of corals in waters shallower than 15 metres. In Fiji, bleaching has struck 65% of the reefs. Similar problems have been reported from Tonga, the Cook Islands and Solomon Islands (Moore, 2002).

Shrinking island populations

Many Pacific Island people are abandoning their islands to live in New Zealand, Australia and the USA.

What is global warming?

Global warming is an average increase in the Earth’s temperature, which in turn causes changes in climate.

Scientists believe that a warmer Earth may lead to changes in rainfall patterns, a rise in sea level caused by slow melting of polar ice, and a wide range of impacts on plants, wildlife and humans.

What about greenhouse effect?

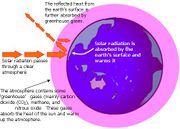

Although some people use greenhouse effect to mean the same thing as global warming, it has a more specific meaning. Greenhouse effect is a natural warming process, in which a layer of ‘greenhouse gases’ in the atmosphere absorbs the heat energy from the sun and keeps the Earth’s atmosphere warm and hospitable for living things (see the diagram on the right). Without this important warming process, life would not be possible on planet Earth.

But why is this natural warming process a threat?

Human activities – especially the burning of fossil fuels (e.g. coal and oil) – intensify the greenhouse effect. These are the three most important greenhouse gases:

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) is released by all living things as a product of respiration. When we burn fossil fuels (particularly in car engines), we also add a lot of CO2 to the atmosphere. Plants use up CO2 during photosynthesis. So when we humans cut down trees around our own homes or cut down whole forests, we increase the level of CO2 in the atmosphere.

- Methane (CH4) is an important part of natural gas. It is also formed when plants decay in places where there is very little oxygen (e.g. wet-rice paddies and landfills). Ruminants (e.g. cows, sheep and goats) release a large amount of CH4.

- Chlorofluorocarbons. A chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) is any compound in a group of manufactured organic compounds that contain chlorine, fluorine and carbon. The two most common chlorofluorocarbons are trichlorofluoromethane and dichlorodifluoromethane. We use CFCs as coolants in air conditioners and refrigerators, and as propellants in aerosol spray products (e.g. insect spray cans).

Other greenhouse gases include nitrous oxide (N2O), water vapour and ozone. Ozone is a form of oxygen. An oxygen molecule (O2) has two oxygen atoms. An ozone molecule, however, has three oxygen atoms, so its chemical formula is O3. In the lower atmosphere (troposphere), ozone is a pollutant because it contributes to global warming. But in the higher layers of the atmosphere (e.g. the stratosphere), ozone is an important gas because it forms a layer (the ozone layer) that protects living things on Earth from the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

It is not only gases that contribute to the greenhouse effect. Other contributors include clouds, soot and dust particles.

Re-orientaing the curriculum to enhance the relevance and inclusiveness of teaching and learning of Climate change

Global warming is a term that many Pacific Island school children (and teachers) have heard of. They may know related terms too, such as greenhouse gases, greenhouse effect and sea level rise, especially from science lessons. However, it is likely that most do not fully understand this natural phenomenon. On leaving school, they remember global warming as just one of those science topics they learnt at school. They have the knowledge to confidently describe how it is caused and how it could be avoided. But there remains some key questions in relation to their learning:

- Do our Pacific Island people understand this natural phenomenon is real and is an imminent threat to our islands, environments, economies, cultures and – most importantly – our very existence as a unique group of people?;

- Do our Pacific Island people understand the relationships between global warming and our life-style, our evolving cultures, our education, economic and political systems, etc.?

Climate change and Education for Sustainable Development

Education is believed to be where a lasting solution to the challenges of global warming and climate change can be found. Pacific Island education has done significant amount of work on climate change mitigation and adaptation. However, the urgency of climate change and the imminent threat it poses to our very existence as an unique group of people, calls not only for new ‘solutions’, but for new questions. We need to understand how well core ideas and skills have actually been understood and practiced by every learner. Further, we also need to understand how the formal curriculum, at all levels of education in the Pacific, has changed in response to climate change.

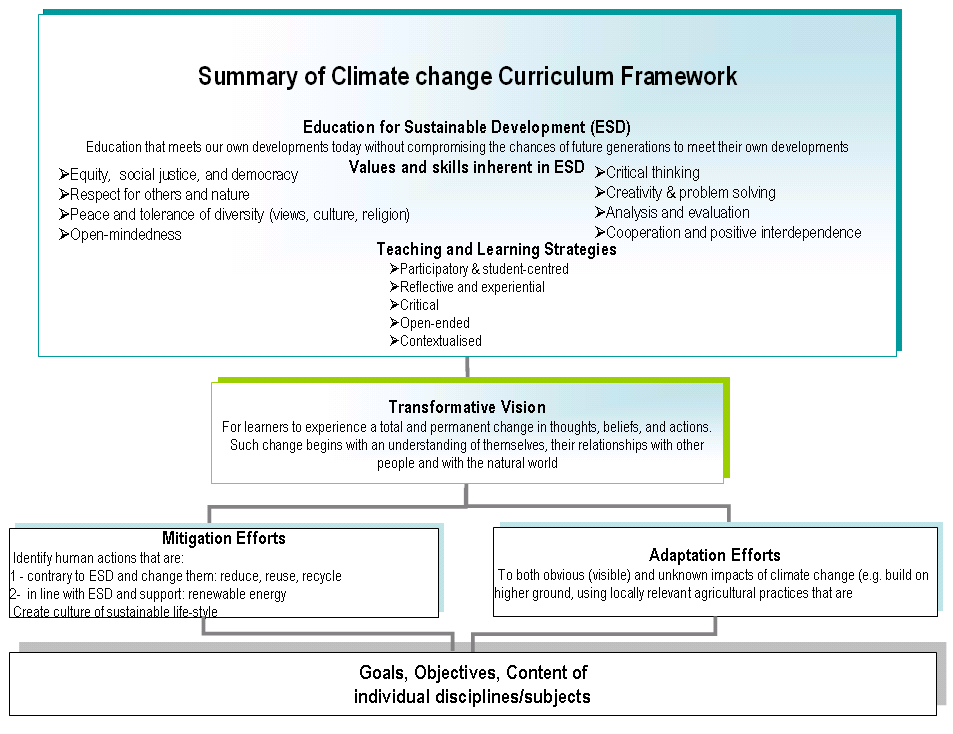

Pacific Island education systems should see climate change as an opportunity to utilize the principle of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to structure a curriculum response to combat climate change. There are numerous successful interdisciplinary climate change initiatives in the informal education sector – in our villages, and communities, in some non-government organizations, and in youth groups. Sadly, however, there is a belief that interdisciplinary efforts to combat climate change have not been too successful in the formal education sector.

The compartmentalization in the existing curriculum on the ground of subject disciplines unavoidably leads to an exam-oriented education system that treats climate change as a ‘science-only’ issue or in some cases an ‘extra-curricular’ component of students’ learning experiences. Regardless of the level of education at which we operate, our hope for successful Climate change initiatives, hinges on the existence of an inclusive interdisciplinary curriculum framework that is grounded on the values and principles of ESD. It is only through Pacific Island people learning to know, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together sustainably that real and fruitful efforts to counter Climate change can ever take place.

The current challenges to effective Climate change curriculum initiatives in the Pacific

Existing Climate change curriculum is not inclusive

The traditional science-oriented focus of the teaching of Climate change, especially in the Pacific secondary school, is discriminatory. In most of the existing curriculum in the Pacific Islands, Climate change is taught mainly to students of Science and Geography. Consequently, the larger proportion of students that do not take these subjects lack the basic understanding and skills relevant to mitigating and adapting to Climate change.

Our perceptions of Climate change Education

The issue discussed above is probably due to a resilient belief that Climate change is only an environmental issue and therefore it should be taught only in the Sciences and Geography. Further, because of this belief, the teaching of Climate change focuses mainly on the scientific facts about climate change – the chemistry, the trends, mitigation strategies, etc. However, there has not been adequate curriculum effort to emphasise the socio-economic nature of Climate change; there is no provision in existing curriculums to address moral issues, human behaviour, and attitude (the core of all problems).

Exam-oriented curriculum

There are excellent existing curriculum initiatives related to Climate change (e.g. Live and Learn environmental programmes, Sandwatch, and ASPnet, SPREP’s educational programmes). But when these efforts, however, reach the formal school setting, most of them are treated as ‘extra-curricula’ activities, and therefore not examinable.

As the greatest challenge of our time, Climate change warrants everyone’s careful attention. The urgency and importance of Climate change must be reflected in all that we do in education. Instead of being treated as ‘unimportant’, Climate change education should take centre stage in our classroom practices, both instruction and assessment.

Re-orienting the curriculum to combat climate change

If the necessary changes in our societies are to be effected in time, our education systems must do everything within its powers not only to speed up our response to climate change but also to ensure that actions taken are sustainable and effective in the long-term.Although we don’t have the advanced technology to combat climate change, our education systems already have adequate knowledge of climate change. We already have the human resources. It is not a matter of lack of knowledge. What we lack is wisdom; we lack the ability to use/create knowledge sustainably. Climate change is one of the consequences of our ‘thoughtless’ creation/using of knowledge.

A re-orientation of the curriculum (using what we currently have) would ensure wise use of knowledge. An effective climate change education curriculum, must:

Focus on transformation

Since climate change is the consequence of human actions, the focus of our education systems must be not only on identifying unsustainable actions but also on transforming them. At the core of this is transforming people’s approaches to life, belief systems, and perspectives. Necessary skills and concepts that would facilitate such transformation need to be included in all subject curriculums. These skills and knowledge include:

- open-mindedness

- reflective and critical thinking

- problem solving

Ensure access for ALL

Re-orienting the curriculum to respond to climate change needs to ensure that learning experiences are available to every learner in all levels of education. Relevant skills and knowledge for mitigation, adaptation, and transformation must be taught in all subjects areas, at all levels, and must be learnt by everyone. It must be a climate change education for all.

Be interdisciplinary in nature

This would provide our people with opportunities to deal with problems (such as climate change) that require many overlapping solutions and to apply their learning in real-life situations.

Ensure coherence and coordination

Current efforts appear to be ad hoc in nature and many appear to cease when funds are no longer available. Different arms of one government would be working one iniative but are totally unaware of similar initiatives that are happening in other arms. Therefore these is a need for careful coordination of these efforts to ensure coherence and long-term impact. For school/university subjects/courses, adequate overlapping (of objectives and content) is needed to promote interdisciplinary thinking and facilitate meaningful application of learnt skills and knowledge.

Assess what we truly value in education (both process and product)

Assessment is an important element of the curriculum. To ensure success and sustainability of this curriculum response, our assessment process must change. Our

I believe that the above features would ensure an interdisciplinary curriculum framework that not only is inclusive but also reinforces the links between science, the environment, and other important areas such as economy, culture, ethics and justice, gender equity, and peace.

This curriculum framework has the quality of penetrating existing arbitrary curriculum partitions. PACE-SD (2007) describes such a curriculum framework as one that has the capacity to “accommodate social, environmental and economic knowledge in an inter-disciplinary manner”.

| For the Pacific to effectively come to terms with increasing need for mitigation and adaptation, we need a transformative curriculum framework that focuses on the integration of the values, principles and practices inherent in ESD into all aspects of learning. The traditional curriculum approach, with its discipline oriented focus and where individual subjects are clearly demarcated, is facing difficulty in addressing the multifaceted nature of climate change. The impacts of climate change challenge every aspect of our being Pacific Islanders; our economies and infrastructure, our health systems, our political systems, our cultures, and our very existence.

ESD provides a framework for inclusive, relevant, and meaningful teaching and learning of Climate change. According to PACE-SD (2007), ESD promotes education in its broadest possible sense. With the realization that environmental problems are closely linked to our economic and socio-culture problems, using ESD to drive our curricular responses to climate change is a "more inclusive approach.” With such broad goals and vision, and especially when it is grounded on the values and principles of ESD, this curriculum framework would help to firmly anchor the four pillars of education in the lives of our people: they learn to know about climate change, learn to do mitigating and adaptation activities, learn to live together with others and share limited resources, and learn to be creative and innovative citizens of the Pacific. |

| *Jane Resture's Website |

Subtopic

Subtopic

References