HIVAIDS/Mental Health and Spirituality/Stigma and discrimination

Contents

Introduction

One of the highest contributing factors to the increased spread of HIV/AIDS is stigma and discrimination. It is very important to learn and understand the consequences of stigma and discrimination within ourselves as well as other people in order not to stigmatise against people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHAs). Let’s start by looking at what stigma and discrimination are, and the different forms they take.

Stigma

What is Stigma?- Stigma is a negative attitude towards a person or group of persons who have, or are perceived to have, a specific characteristic

- Stigma is an act of identifying, labelling or attributing undesirable qualities to those who:

- Are perceived as being different or deviant from the social moral code

- Elicit fear because of lack of information

- Seen as a drain on resources

- Stigma is a social process and may be layered onto other forms of inequality such as:

- Class

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Sexual orientation

- Gender

- HIV/AIDS status

- Nationality

- Social Status

- Demographic Positioning

Stigma can be enacted or felt.

| Enacted | Felt |

| When stigma is enacted, it has moved from a negative attitude to an act of prejudice or discrimination. This stigma has an external and actual source and sometimes extends to the family or friends of the person being stigmatised against. | Felt stigma is an internal feeling of being mistreated by society due to a condition. It is caused by a fear that discrimination may occur which results in a range of self protective behaviours such as the avoidance of certain situations, people or places. This person feels blamed and shamed but may not actually be treated this way. |

Discrimination

- Discrimination refers to negative behaviour towards someone based on any grounds or qualities such as class, race, ethnicity, HIV/AIDS status, gender, sexual orientation, age, etc;.

- Discriminative behaviours can be categorised as either passive or active

- Discrimination occurs when people are treated with less respect or worth than they deserve due to any of the above mentioned characteristics;

- Discrimination can involve the distinction, exclusion, or preference of a person;

- Discrimination plays a role in diminishing equal enjoyment or exercise of all rights and access to public or private services and can take the form of any of the following:

- Verbal and physical harassment including death threats

- Denial of access to public or community services and health care services where they may experience discriminatory attitudes or separation from the ‘normal patients’

- Avoidance and neglect in the workplace, sometimes resulting in a person living with HIV being laid off or fired

- Eviction from homes

- Abandonment by partners and spouses

- Pre-employment screening or testing

- Social isolation and avoidance, for example, being forced to live in outhouses

- Refusal by health care workers to treat patients because of their HIV status and lack of confidentiality (to alert others of infection)

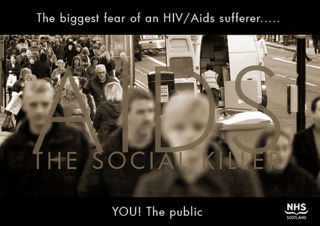

Stigma, discrimination and HIV/AIDS

There is a great deal of stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS. People living with HIV are often discriminated against and treated with fear and loathing.

The following points outline some of the reasons why there is so much stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS.

- People living with HIV/AIDS, or those who are believed to be living with HIV/AIDS, or those close to them, are often seen as having a characteristic which stigmatises and discredits them.

- HIV/AIDS is considered to carry a double stigma: a terminal illness and a sexually transmitted illness.

- HIV is often associated with behaviour which is already stigmatised, such as “promiscuity”, homosexual sex or sex work.

- Sexually transmitted illnesses are thought to be harboured by individuals who are deviant, unnatural, and who participate in socially “undesirable” activities, such as homosexuality, drug use, multiple sexual partners and sex work.

- HIV is seen to be avoidable' and infection is viewed as resulting from “irresponsible” behaviours or choices.

- People living with HIV/AIDS may look very sick and fear of others becoming infected is perceived due to lack of information on how the disease is contracted.

- It can be fatal and therefore inevitably causes fear.

- People living with HIV may be seen as a drain on resources.

- Stigma and discrimination can be very harmful to the individuals discriminated against, as well as to their family, community and society as a whole.

- Enacted or felt stigma and discrimination often results in a person being afraid to disclose their status. Thus disclosure is often avoided. Disclosure can result in job loss, partner abandonment, social ostracism, personal injury, refusal of medical treatment, refusal of insurance and death.

- Stigma and discrimination results in a number of exclusionary behaviours towards people thought to be HIV positive, ranging from subtle neglect to overt ostracism and discrimination (enacted stigma).

- Stigma and discrimination results in negative media representations and language – for example in South Africa there are the terms such as “ingculazi” which means ‘associated with germs’ and “gawulayo” which means ‘the disease that decimates’.

- Sigma and discrimination results in blame which in turn could lead to a distinction between those who are “innocent victims” such as children or recipients of blood transfusions and the “guilty” who contracted HIV through their own actions.

- Stigma and discrimination undermines social cohesion by isolating, dividing and breaking down communities.

- Stigma and discrimination undermines the basic value of equal human rights.

- Stigma and discrimination results in the internalisation of shame and blame and strategies to reduce this, including avoidance and withdrawal from society and relationships, self exclusion from services and opportunities, negative self perceptions, overcompensation and fear of disclosure.

- Stigma and discrimination undermines public health goals by decreasing access to HIV prevention options and voluntary counselling and testing, as well as decreasing access to treatment, support and welfare options for those who are living with HIV.

Fear of Stigma Fuels the HIV Epidemic

- Stigma is of utmost concern because it is both the cause and effect of secrecy and denial, which are both catalysts for HIV transmission. Fear of stigma limits the efficacy of HIV-testing programs across sub-Saharan Africa, because in most villages everyone knows sooner or later who visits test sites. While in some places the advent of free and accessible antiretroviral therapy has offered hope and encouraged people to go for testing, stigma remains a barrier to testing even where treatment is available. Without HIV testing, an essential first step to treatment, years may go by while people who are infected transmit the virus to others. When individuals finally become ill and seek care, treatment as a prevention strategy has lost much of its potential effectiveness.

- Fear of stigma can cause pregnant women to avoid HIV testing, the first step in reducing mother-to-child transmission. It may force mothers to expose babies to HIV infection through breast-feeding because the mothers do not want to arouse suspicion of their HIV status by using alternative feeding methods. Fear of stigma, and the resulting denial, may even inhibit condom use in HIV discordant couples. Further evidence of how stigma leads to denial is the way in which newspaper obituaries avoid mentioning HIV/AIDS as a cause of death.

- HIV-related stigma directly hurts people, who lose community support due to their real or supposed HIV infection. Individuals may be isolated within their family, hidden away from visitors, or made to eat alone.

- These repercussions may or may not be simple acts of heartlessness. They may be a well intentioned but ignorant attempt to preserve the family. In the community, the entire family may be sanctioned because one member is ill; in an impoverished society with no safety net of public services, this can be ominous for everyone.

- In many African villages, an individual’s, and a family’s, life is closely intertwined with others. The same people have lived closely together for several generations, and there are few secrets. Inside families, caregivers may be largely concerned about contracting HIV through casual contact, and outside they fear the gossip that can greatly affect everyone’s social standing. Neighbors and other customers, for instance, may refuse to purchase vegetables or poultry from someone associated with HIV.

- In impoverished areas, this can devastate a family’s chances of economic survival. The language used to describe people living with HIV (such as “she is an HIV”, “he is a walking corpse”) clearly conveys stigmatizing attitudes.

- A particularly powerful example of stigmatizing language is found in parts of Tanzania, where an HIV-positive person is called nyambizi, or submarine, implying that the HIV-positive person is stealthy, menacing, and deadly. People living with HIV can also experience a form of internalized stigma. Even without the burden of externally imposed social opprobrium, those living with a serious illness can face an enormous and painful inner struggle. They may eventually cease to be who they were, instead becoming a unitary “person with an illness” or—more damning—an “ill person,” a thing in which personhood and illness have completely fused.

- The philosopher Simone Weil characterized this assault of illness upon the self with the classical Greek notion of the soul—Malheur (affliction) stamps the soul to its very depths with scorn and disgust.

- The combination of external stigma and internal oppression of the self may impose a heavy burden. In our experience of working with people with HIV in Africa, the result of this burden is often a downward spiral marked by fatalism, self-loathing, and isolation from others. And by shaming and silencing the very people who could credibly speak for HIV prevention and provide care for HIV-positive others, stigma fuels the HIV epidemic, consigning more people to suffering and death.

Stigma in Society

- Stigma is part of the attitudes and social structures that set people against each other. It impedes any countervailing forces for social equality. Certainly since Erving Goffman’s seminal work on stigma in the early 1960s, stigma (plural stigmata) has been recognized as “an attribute that is signifi cantly discrediting,” and it is known as a potent and painful force in individual lives. Fueled by prejudice and appealing to it, stigma functions to diminish the person or group being targeted. Some commentators since Goffman have particularly examined stigma’s broader social functioning. They have noted that while subordinating individuals or groups in society, the stigmatizing process also reinforces hierarchical patterns of privilege, where those at the top of a stratifi ed society are pre-eminent over, and sometimes predatory upon, others at lower levels.

- To see this perhaps more clearly, think of certain religious settings where punishment theories of illness causation are in force. One such outlook presumes an aroused deity or ancestor bringing illness upon a person in retribution for an offense. This notion stigmatizes people struggling with their illness.

- It blames their sickness upon misbehaviors, while at the same time it rationalizes privileging the well over the ill. Punishment theories authorize communities to isolate or purge the “impure”—people whose illness or imagined “sinfulness” would contaminate the whole—while reassuring that virtue and social status will protect the righteous.

- Clergy and other religious leaders are as susceptible as any to the temptation to exercise power over others. This imbalance of power is facilitated by such structured inequalities within churches as the preeminence of clergy over laity, of men over women, and even by the presumed superiority of the more “spiritual” over the less so. Under the influence of western missionaries, many African Christian organizations still promote evangelical formulae in which, it is taught, creation was originally good, but then the “fall” of humankind occurred, which is bad, and finally, redemption is available only for the chosen. This theological approach warrants valorizing or stigmatizing people as “saved” or “sinner,” “pure” or “impure,” “us” or “them,” and it strengthens the broader social stratifications within which stigma flourishes. What is weakened is the opportunity to apply healing insights from the rich Christian legacy of compassion, liberation, and hope.

Gender and HIV

- In much of sub-Saharan Africa, women are a subordinate group who are expected to become pregnant, bear children, and fulfill the sexual desires of their husbands without hesitation. Such traditional assumptions, sometimes reinforced by the missionary religions, greatly benefit men while predisposing women to HIV infection. Often husbands carry HIV, while barrier methods of disease prevention, such as condoms, are proscribed, perhaps most vigorously by male-dominant religious organizations. In addition to women’s subordinate status in many societies, they are also frequently stigmatized as the vectors of HIV transmission, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

- In Malawi, the term for a sexually transmitted disease, regardless of its origin, is “woman’s disease.” Husbands have beaten and/or abandoned wives thought to be HIV positive, despite the fact that many women contract the virus from their husbands. Some women are subject to violence if they refuse a sexual overture, ask their husband to use a condom, or request an HIV test. If a husband should die, the wife’s in-laws may seize her inheritance. A woman exhibiting the independence needed to protect her health and selfesteem risks the disapprobation of her family and of the community.

- Men are the clear winners of this arrangement in both social and economic terms, and many widows and their children, dispossessed or not, struggle against enormous odds simply to survive. Public attitudes, stigma among them, help to sustain the entire unjust system.

Violation of Human Rights

- As noted, HIV/AIDS-related stigma often leads to HIV/AIDS discrimination. This, in turn,leads to the violation of the human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS, of their families and even of those presumed to be infected, such as family members or other associates. Freedom from discrimination is a fundamental human right founded on principles of natural justice that are universal and perpetual. Human rights inhere in individuals because they are human, and they apply to all people everywhere. The principle of non-discrimination is central to the human rights thinking and practice. The core international human rights instruments prohibit discrimination based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

- The United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in its resolutions, has declared that the term ‘or other status’ in the various international human rights instruments should be interpreted to cover health status, including HIV/AIDS. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights has further confirmed that discrimination on the basis of HIV/AIDS status (actual or presumed) is prohibited by existing human rights standards.

- Discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS, or those thought to be infected, is therefore a clear violation of their human rights. But why is it important to recognize the links between stigma, discrimination and human rights violations? There are several reasons:

- Firstly, because stigma, discrimination and human rights violations are interrelated. They create, reinforce and legitimize each other. They form a vicious circle.

- Secondly, since freedom from discrimination is a human right, there are already existing frameworks for responsibility and accountability of action. Human rights derive from the relationship between the individual and the State. They arise from the legal obligation of States to regulate the relationships between their citizens. Thus, States are responsible and accountable, not only for directly or indirectly violating rights, but also for ensuring that individuals can realize their rights as fully as possible. States have the obligation to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

- In relation to discrimination, the obligation to respect requires States not to directly or indirectly discriminate in law, policy or practice. The obligation to protect requires States to take measures that prevent third parties from discriminating, and the obligation to fulfil requires States to adopt appropriate legislative, budgetary, judicial and other measures to ensure that strategies, policies and programmes are developed to address the discrimination and to ensure redress to those who have been discriminated against. The existence of HIV/AIDS-related discrimination is a litmus test for the lack of respect, protection and fulfilment of human rights.

- A human rights framework provides avenues for people who suffer discrimination on the basis of their actual or presumed HIV-positive status to have recourse through procedural, institutional and monitoring mechanisms. Since HIV/AIDS-related discrimination constitutes a violation of human rights, persons who discriminate are accountable by law and redress can be provided, where appropriate.

- Procedural, institutional and other monitoring mechanisms exist to ensure accountability at national, regional and international levels. At national level, these include courts of law, national human rights commissions, ombudsmen, law commissions and other administrative tribunals. For example, the National Human Rights Commissions of South Africa, Ghana and India and the Ombudsman of Costa Rica have undertaken various activities to promote and protect HIV/AIDS-related rights in their countries.

- Beyond legal redress, there are many other ways of tackling HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Public information campaigns, for example, have an important role to play in helping people understand the unfairness and unjustness of stigmatization and discrimination.

- They can also change individual and social attitudes. Participatory education can help individuals place themselves in the position of someone who has suffered discrimination and thereby appreciate the injustice of discriminatory actions.

- Through grass-roots activism, advocacy and involvement in the development and implementation of policy, the actions of people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS can be a radical force for change, breaking down the barriers to the full realization of human rights. It is important, during and beyond this campaign, to ensure that all forms of discrimination that fuel the epidemic are equally addressed and action taken. The campaign must move beyond the documentation or flagging of the issue to creating positive role models and encouraging positive action.

Effects of stigma and discrimination on adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART)

- Stigma is believed to be one of the greatest barriers to HIV treatment. It has been said to foster the growth of the epidemic as prevention efforts are undermined due to people’s reluctance to get tested, and unsafe and risky behavioural patterns are perpetuated (UNAIDS and WHO 2003)

- It has been suggested that the provision of ART as part of a comprehensive treatment package would signify a move towards people becoming more open and combating stigma.

- Stigma is in itself a difficult concept and even more difficult to measure. Stigma manifests in a multitude of ways, sometimes enacted, sometimes felt, sometimes applied to oneself.

- Discrimination is often the physical action undertaken as a result of stigma existing. It may occur within the household, in the workplace, in the community or even at the health service site.

- In a study undertaken in a workplace in South Africa, health care workers reported experience of stigma due to their involvement in treating those thought to be HIV positive. Similarly any worker showing an interest in the epidemic would be cross-questioned as to why they were interested and whether they were HIV positive.

- Shame and secrecy works against adherence to ART because privacy is sought and medicines have to be kept hidden.

- It therefore makes it difficult to take doses at the right time of day, especially for those who feel the need to hide their status from people at work or in the home.

- Successful adherence to ART is largely dependent on a culture of acceptance and openness, which makes good treatment outcomes much more achievable.

- The prevalence of misinformation about AIDS in South Africa has not only hampered efforts to increase access to treatment, but has also created a climate of confusion in which prejudice towards people living with HIV thrives.

- HIV is sometimes seen as being a disease of the poor. In South Africa, there is some correlation between extreme poverty and high HIV prevalence, although HIV is prevalent across all sectors of society.

- In 2000, Justice Edwin Cameron of the South African Court announced in a speech that he was HIV-positive. The public response to this declaration was, on the face of it, largely supportive. However, coming out as HIV-positive can in many cases have a negative effect on employment and housing opportunities, as well as social relationships.

- When his son died of AIDS in 2005, Nelson Mandela publicised the cause of his death in an effort to challenge the stigma that surrounds HIV infection: "Let us give publicity to HIV/AIDS and not hide it, because [that is] the only way to make it appear like a normal illness."

|

So, do you have any negative attitudes to certain people, and especially those living with HIV? Do you treat EVERYONE with respect and dignity? Do you have hidden insecurities about HIV/AIDS and those living with HIV? Take a look at the following people and indicate who you would have the least or most sympathy for if s/he had become HIV positive. |

| Situation | Least | Most |

| A married man. | ||

| A new-born baby. | ||

| A homosexual male. | ||

| A sex worker. | ||

| A church leader. | ||

| A business man. | ||

| A young girl. | ||

| A drug user. |

Now, try this exercise...

Indicate which of the following people you would have the least or most sympathy for if s/he had become HIV positive.

| Situation | Least | Most |

| A married man infected by his wife. | ||

| A new-born baby infected by her mother. | ||

| A homosexual male infected by his doctor. | ||

| A sex worker raped by someone who was HIV positive. | ||

| A church leader who is unknown. | ||

| A business man infected by a blood transfusion. | ||

| A young girl who is promiscuous. | ||

| A drug user infected by her first boyfriend. |

Interesting isn't it, when you really analyse your responses? Sometimes our attitudes are shaped by the context of the situation. With regards to HIV/AIDS, we should be free from any stigma and discrimination, regardless of the context. Perhaps a personal challenge that we all need to work on!

Strategies to combat stigma and discrimination

Successful strategies to reduce and stop stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV needs to include social, legal as well as psychological components in order to be more successful.

Social components

- Promoting information and awareness campaigns to reduce ignorance about the disease to tackle fear and prejudice

- Promoting personal contact with someone living with HIV/AIDS

- Having a person living with HIV/AIDS share their experiences can assist to dispel myths about HIV/AIDS and generate understanding and support

- Training health workers to sensitise them and create awareness on how to respond to the disease. This would dispel fears about occupational risk and promote the use of universal precautions.

- Challenging cultural organisations, traditional leaders and healers, community leaders and faith organisations to provide positive and accurate messages about people living with HIV.

- Working with media houses and practitioners to promote non-discrimination and the use of appropriate language.

- Encouraging government workplaces to offer leadership and provide role models who promote non-discrimination.

- Providing good treatment and care, including access to ARVs, so that people living with HIV can work and be independent and are not seen as a drain on resources.

- Ensuring that gender issues are included in all stigma and discrimination reduction strategies. Stigma and discrimination around HIV/AIDS is often more against women. This is because women are often blamed for sexual illnesses; are seen as carriers of diseases; the expression of their sexuality is seen as bad and immoral; or as sex workers they are seen as responsible for the HIV epidemic. These negative attitudes towards women and their sexuality often result in double stigma, and incur more discrimination against them. In addition, because women are tested when they are pregnant they are more likely to be identified first as the HIV positive partner in a relationship. This makes it easy to blame them for bringing HIV into the relationship.

- Some suggestions to reduce this double stigma against women include:

- Making a conscious effort to examine your own gender attitudes and stereotypes

- Making sure you are informed about how gender roles are constructed and the impact it has on women – for example are they always able to protect themselves in relationships?

- Challenge sexism when you see it in the HIV/AIDS context

- Challenge any beliefs about HIV/AIDS that appear to blame women

- Seek to empower women and girls, but not at the expense of men – gender power relations should not be seen as a desperate struggle to seize power but rather as an opportunity to share and benefit from this sharing

- Challenge gender stereotyping of men as well as women – it is unhelpful to see men as simply “perpetrators” and women as “victims".

Legal components

- Promoting the importance of confidentiality and readiness to disclose.

- Ensuring that workplaces conform to laws and codes of conduct around HIV/AIDS.

- Using anti-discrimination legislation to address acts of discrimination.

- Making people aware of their rights.

Psychological components

- Providing support systems, including individual counselling and support groups, for those infected and affected by HIV to create an enabling environment for disclosure.

- Providing more positive role models for people living with HIV.

- Providing opportunities to people living with HIV for self development.

- Developing media-savvy people living with HIV so that they know how media houses and practitioners operate. This will allow the use of every media interaction as an opportunity to challenge the stereotyping of people living with AIDS and to fight for the right of people not to be reduced to a virus or a disease.

CHALLENGE STIGMA AND DISCRIMINATION!!!

|